Discovering a 12th century herbalist in Nazi Germany

The overlooked story of a nun who was a mystic, an anchoress, and more

When writing historical fiction set in Nazi Germany, you wouldn’t think a tome written by a 12th century Christian mystic would be relevant. And yet, for me, it was.

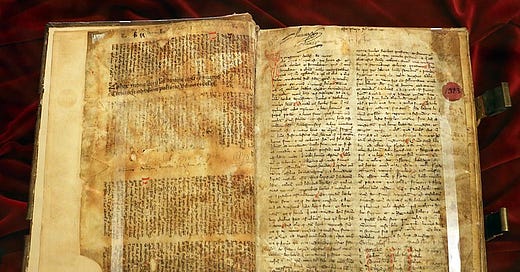

When I decided that my main character in To Look Upon the Sun would be a burgeoning herbalist, I looked to Germany’s tradition of plant medicine. That’s when I discovered Hildegard von Bingen and her book, Physica. Finding this book was a gold mine for a writer like me, who’s obsessed with forgotten women throughout history.

Hildegard was a German nun, mystic, composer, and healer who lived a long and fascinating life. The youngest of ten children, her parents gave her as an oblate to a monastery when she was eight years old. Only a few years later, she and her abbess became anchoresses—which meant they were permanently enclosed in a room with only a small opening to pass food through. She was essentially buried alive as an act of devotion, though she would have been too young to make that choice for herself.

She wouldn’t leave that room until the abbess died years later, and Hildegard became the mother superior of her community.

Hildegard said she began experiencing visions from a young age, and they continued throughout her life.

And I saw a light-filled man emerge from the aforesaid dawn and pour his brightness over the aforementioned darkness; it repulsed him; he turned blood-red and pallid, but struck back against the darkness with such force that the man who was lying in the darkness became visible and resplendent.

She wrote several books documenting her visions and composed haunting music which is played to this day. By all accounts, she was a force to be reckoned with.

To lend credibility to her work in a world of men, she slyly belittled herself for being a woman, and men paid attention to what she had to say because they believed it came straight from God, via her visions. She became quite influential in her day. Well played, Hildegard.

Physica is different from her other books in that it’s sourced from her personal experience as a healer. There were no visions involved. It describes the medicinal properties of not just plants, but animals and minerals.

I like Hildegard’s approach because it’s holistic. She speaks of Viriditas, or greening power, achieved by finding balance.

However, some of her treatments now seem absurd, such as this one for linden’s “very strong power against all diseases”:

In the summer, when the tree is green, take the bark away from the rootstock, not the branches, until you come to white wood. Then cut a sliver from the wood, and place it into a hole bored into a golden ring. Over this wood splint place a green glass, and no other stone. Put a spider web, cotton, or wool between the splint and your finger…

She was also perhaps the first woman in Europe to write, in coded language, of pregnancy termination. Her cures were for women “in pain from obstructed menses,” and she prescribed an elaborate treatment involving the cooking of herbs in “water from a freely flowing stream, which is tempered by sun and air.” She then advised the woman to take a bath while sitting on the herbs, and then make a claret out of additional herbs.

At first, I was surprised that no one accused her of witchcraft, but I learned that in the 12th century, the distinction between science, magic, and miracles wasn’t as pronounced as it later become, from the 15th century on.

In my novel, the main character, Ilse, brings Physica with her on all her journeys. It’s her link to her mother, to whom it once belonged, and to all women who’ve used plants to take back some power and control over their bodies back from the men in their lives.

As Ilse matures and learns from the tumult of her life, she becomes more of an herbalist, too, finding answers and escape in the pages of Physica.

My thanks to Hildegard, who received her long overdue canonization in 2012.

To read a novelization of her story, which I understand to be largely accurate, check out Illuminations by Mary Sharratt.